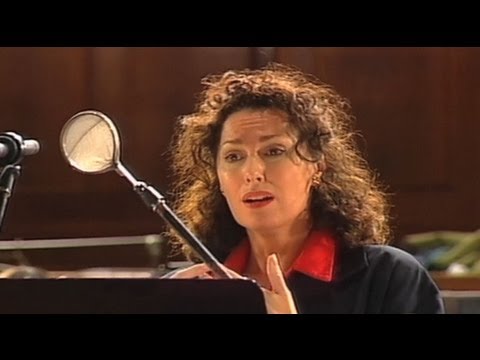

JOAN HAMMOND – A PERSONAL TRIBUTE

Joan Hammond was a remarkable woman. With remarkable talents. She was a champion golfer, a career violinist (with the Sydney Philharmonic, later the Sydney Symphony Orchestra), a respected journalist and, after retiring from performing, was a highly-regarded teacher and a prominent advocate for opera in her native Victoria. But her real gift was for singing; her voice celebrated in the major concert halls and opera houses of the world; her many recordings an invaluable and abiding legacy.

Ironically, we may never have heard Hammond sing at all, were it not for a childhood cycling accident that resulted in her left arm being two inches shorter than her right. Just three years into her orchestral career, the pain caused by the physical demands of her constant playing proved too much to endure and ended her life as a violinist. Ever-ready, characteristically, to adapt to new circumstances, Joan turned to singing and went to Vienna to study and, from there in 1936, to London. She stayed in the British capital for the next quarter-century, pursuing a career that, at its pinnacle, saw her hailed as ‘Britain’s favourite singer’. Within just four years, the legendary record producer Walter Legge, to whom Joan’s recording career was indebted, declared that she was ‘the best of the younger generation of sopranos in Britain’. (Much later, she would become the second of only three Australian singers, after Nellie Melba and before Joan Sutherland, to be created a Dame.)

Joan was born in Christchurch, New Zealand on May 24 1912. She moved to Sydney as a baby, and it was there she was educated and began her working life. At the age of 24 she travelled to Vienna to study singing; the venture funded largely by Australian women golfers in recognition of the many championships and titles she had earned in her youth. In 1949, she fulfilled a long-standing promise to acknowledge her golfing colleagues’ support by returning to Australia at her own expense to sing what she called her ‘Thank You’ concerts. Their success helped to repay her life-long sense of gratitude by establishing a fund that enabled a team of Australian women golfers to play in the British Open Golf Championship for the first time.

While Joan was studying in Vienna, Florence and London, she sang Nedda (Pagliacci), Martha (Flotow) and Konstanze (Die Entführung aus dem Serail) at the Vienna Volksoper, made her London debut recital at the Aeolian Hall, and sang Handel’s Messiah conducted by Thomas Beecham. She went on to sing Mimì (La bohème) and Violetta (La traviata) at the Vienna Staatsoper —the beginning of a three-year contract during which time she was also engaged by the Aussig Opera, Austria —before opening the 1939 Proms in London.

Joan’s next significant UK appearances, with the Carl Rosa Opera company, occurred between 1942 and 1945 when she sang the title roles of Butterfly and Tosca, as well as Violetta (La traviata), Marguerite (Faust) and the Marschallin (Der Rosenkavalier). By the end of the Second World War, her many opera and concert appearances and BBC broadcasts, together with a busy recording schedule, had made her a household name.

Her flawless diction, warm tone and rock-solid technique, together with the strength and beauty of her seductive, vibrantly expressive voice, gave Joan an extraordinary ability to communicate with an audience.

Joan’s recording career began on the Columbia label in 1941 before transferring to His Master’s Voice two years later, always singing, as was the patriotic requirement of the time, in English. It was not until 1947 that she began to record arias in their original languages.

She made best selling recordings of popular arias such as ‘Love and Music’ (‘Vissi d’arte’) from Tosca, ‘One Fine Day’ (‘Un bel dì’) from Madama Butterfly, and ‘They Call Me Mimì’ (‘Mi chiamano Mimì’) from La bohème. Her success with ‘O Silver Moon’ from Dvořák’s overlooked opera Rusalka (Track 5) was such that Sadler’s Wells staged it in 1959 leading a worldwide revival of the work. Lauretta’s then equally unknown aria from Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi, ‘O My Beloved Daddy’, (‘O mio babbino caro’) was first released as the B-side to Tosca’s ‘Love and Music’ on 78 rpm. The coupling became the first operatic recording to sell more than one million copies and went on to win a gold record in 1969. It has never been out of the catalogue since.

Joan made her Covent Garden debut in 1948, singing in productions of Il trovatore, Aïda, La bohème and Fidelio, and made her American debut the following year with the New York City Opera singing in Butterfly, Aïda and Tosca. In 1957 she created an international sensation when she became the first British-based soprano to be invited to sing in Russian in Russia, where she sang Tatyana in Yevgeny Onegin (Track 1) and Aïda (in Italian) at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre as well as in Leningrad.

Audiences loved Joan not just because of her artistry, but because she made the effort to find and visit them. Her touring schedule was often long and gruelling and her willingness to visit smaller cities and towns took her to all points of the compass across the world.

She was a regular guest artist at the world’s great opera houses, and commanded a substantial repertoire of 40 roles drawn from 39 operas. In addition, she sang 27 different masses, oratorios and orchestral concert pieces—including Beethoven’s two Masses, Handel’s Messiah and Mendelssohn’s Elijah —and appeared with the cream of conductors of her time, including Furtwängler, Beecham, Klemperer, Ormandy, Boult, Koussevitsky and Sargent.

Joan withdrew from performing in 1965 following a mild coronary and angina attacks, to settle into semi-reclusive retirement in the splendid isolation of Aireys Inlet, west of Melbourne. From there she proved a vociferous champion for the establishment of the Victoria State Opera company. She became its first Patron and, from 1971-76, its Artistic Director, remaining on its management Board until 1985.

From 1975-89, Joan headed the then newly-formed Victorian College of the Arts’ Vocal Studies department and remained a vocal consultant there from 1990-93. She concluded her teaching career at the University of Melbourne and gave private lessons to a small group of exceptionally talented students, including Peter Coleman-Wright, Steve Davislim and Cheryl Barker.

The loss of her Aireys Inlet home in the devastating Ash Wednesday bushfires of 1983 left Joan homeless and robbed her of a lifetime of mementos. Immediately, fans from all over the world sent their own memorabilia to her—opera and concert scores, sheet-music, recordings, programs, photographs, press clippings and even a replacement Gold Record Award poured in, none more poignant than a large envelope simply addressed to ‘Dame Joan Hammond, Opera Singer, Australia’, which easily found its way to her.

While Joan could be a somewhat formidable person to those who did not know her well, to those who enjoyed her trust she was open and loving. She was a deeply affectionate and emotional woman with fearless integrity, a tolerance of other people’s foibles and a sparkling and irresistible sense of humour.

Her life was enriched by Lolita Marriott who was, like Joan, a talented golfer. They met in 1931 and, following Joan’s return to Australia for the first of two gruelling national tours—in one of which she gave more than 40 performances—Lolita returned with her to London in 1946. They remained inseparable until Lolita’s unexpected death in 1993.

Joan was honoured four times by the Queen; receiving a Coronation Medal and OBE in 1953, a CBE in 1963, a CMG in 1972 and, finally, a knighthood in 1974.

Peter Burch AM BM

Peter Burch AM BM was a lifelong friend of Joan Hammond and served as her Power of Attorney.

JOAN HAMMOND

Call to mind, if you will the love duet that brings to an end the first Act of Madama Butterfly. Find, as a point of entrance, the moment of stillness a few minutes away from the climax, when Butterfly looks around at the heavens above and marvels at the stars, like so many eyes looking down upon them, herself and her lover: never have they seemed so numerous or so beautiful, her lover, Lt. B. F. Pinkerton, looks also, and, despite his impatience to go indoors, he too is rapt with the wonder of it. ‘E notte serena,’ he sings, and his voice soars passionately to the high A. He repeats the phrase, but this time Butterfly joins him, seized by an impulse of rapture. She joins not as he strikes the note but a half-beat later. I remember the first time I saw the opera. I was very young but knew the duet from gramophone records. The delayed entry was not unexpected but I was still unprepared for the effect. The tenor was (in my view) a little shrimp of a fellow with a voice to match, certainly nothing to compare with the Italians whose swelling tones I knew from the records. When Butterfly entered in that phrase, I nearly jumped out of my seat.

And that was my introduction, not only to Madama Butterfly ‘in the flesh’, but also to Joan Hammond. And perhaps I should not have isolated that single note for it came towards the end of a long Act during which we had heard much else from the soprano. The effect of that moment was in fact contingent on all that had gone before: it came as a climax (up to that point) and a kind of vindication.

This Butterfly had been vocally lovely from the very first sounds of her voice heard from off-stage. I don’t think she opted for the high ending, the D flat (and I don’t think she should have for it anticipates the end of the Act). And I can’t say that she looked the part of the 15-year-old girl, but her movements were graceful and her acting carried conviction: I never felt any lack of verisimilitude or (even in ‘One fine day’) that it was just a matter (as is so confidently reported of ‘old’ singers by people who never saw them) of ‘stand and deliver’. Her sung words also were very clear, and she had a way of inflecting the musical expression so that their meaning, even their natural speaking tone, cut through the literary pretensions of the English translation. My introduction to this singer had clearly been an introduction not only to a voice but an artist.

And then there was this always tricky and nervous question of the relationship between the art (as expressed through the voice) and the recordings. Already, even in youth, I had learnt that you could not assume that voices would sound ‘live’ as they did on record. With Joan Hammond, before having heard her that night, I would have said that hers was a very faithfully recorded voice. We all knew her first records, played over the radio: the arias from La bohème and Tosca and the little solo from Gianni Schicchi that she had made so famous. They were resonant, with a lifelike sense of space rather than the studio-bound acoustic of so many. But shortly after the Butterfly evening, when I was still boring my family with her praises, a record of Joan Hammond was played, again over the radio. Keenly appraising ears were turned, and—who has not had this experience?—I felt sadly let down. ‘It’s not what I would call a pretty voice,’ said one. Well, I could live with that, but ‘strident’ contributed another. I felt that was hard but not without justification. ‘I’d call it screeching,’ said a third, at which I left the room.

But certainly there was a discrepancy. I couldn’t say, ‘Well, it doesn’t sound like her’ because for sure it didn’t sound like anybody else. But re-phrase that sentence to something like ‘She doesn’t sound like that’, and there would have been some truth in it. The voice I heard in the free space of the large theatre had been reduced, its power concentrated in the way that a beam of light can be stripped of its diffusions. Or, put it another way, there was less flesh on the bone, less generosity to the sound. This is an effect usually associated with the re-mastering of 78s and LPs in transfer to CD, and indeed I have found it to be a failure common to many transfers of Hammond, as of other singers, but here it seemed already inherent in the recording. This is a caution that needs making for those who come upon the records for the first time and who may wonder. After all, the number of us who can tell what they remember from hearing the voice live diminishes.

Subsequent visits to the Carl Rosa Opera when Hammond was their guest-artist confirmed faith in those glowing first impressions. She also toured in recital, and I remember the unmistakably personal inflections of her voice in songs such as Hamilton Harty’s The Sea-Wrack and Cyril Scott’s Don’t come in, sir, please! She was very good at making the impulsive admonitions of that last song seem spontaneous and colloquial, while infusing the recurring phrase ‘and love you as I may’ with implications of sensual promise. I don’t believe she recorded either of these, but she also sang, with much warmth, The Green Hills o’ Somerset (Track 11), her recording of which became something of a best seller, and which Cheryl Barker includes in the present programme.

For a few years after this, I lost touch with Joan Hammond both in the opera house and concert hall but noted that her record company had promoted her to celebrity-status. It was in these post-war years that the opera houses of the world opened their doors to her. She enjoyed a particular success in Vienna, where she had sung with acclaim in the early days of her career before the war. When I next heard her it was at Covent Garden in Il trovatore.

It struck me that the voice, though still beautiful, had lost something of its visceral force. The best of her Leonora (as with other and still more famous ones, such as Zinka Milanov) was heard in Act 4. The last scene, with Walter Midgley as her winningly lyrical Manrico, made an enduring impression and, like all Leonoras worthy of the part, she made a particularly lovely thing of the rising phrases of ‘Prima che d’altri vivere’. One can delude oneself in such matters, but I seem to hear her in that even now. She had a very personal style, which some held against her, of singing a kind of emphatic legato—which sounds like a contradiction in terms but may be (I fancy) the effect composers sought when they wrote a series of notes with staccato markings yet with a broad ‘binding’ phrase-mark over all. At any rate, as critics of that time who knew about such things were always pointing out, it was ‘not Rethberg’.

That was a reference to the soprano of inter-war years, Elisabeth Rethberg, whose method was, rightly I think, held to be a model of ‘classic’ style and voice-production. Hammond was constantly used as a target in discussion at that time about the inferiority of modern singers in comparison with the great ones of the past. I engaged in a controversy, a little exchange, in The Record Collector magazine, where a passing reference I had made to Hammond in relation to Melba was immediately slapped down. ‘In the matter of repertoire you can take your choice; in the matter of tone there is no choice’, was one assertion. I wasn’t convinced. In as far as the quality of a singer’s tone is judged by the absence or presence of an impure alloy, an extraneous, metallic element that, to my ears, spoils so many good voices, Hammond’s tone was always pure. I don’t remember that she ever acquired that kind of impurity.

There was certainly a loss of volume. The last time I heard her was at Sadler’s Wells in London in Dvořák’s Rusalka (Track 5), and by then the cutting-edge had been dulled. A certain sweetness and the ability to float high notes had remained. But the experience was not a happy one. Much better to remember in these late years is a performance of Verdi’s Requiem at the Albert Hall. Gigli was the tenor, the mezzo Ebe Stignani, the bass Italo Tajo. But the best singing was Hammond’s, lovely in the ‘Libera me’, and sometimes (as in that long-held E natural) breathtaking in control.

Memories are now for a relative few; for everyone there remain the recordings, and a book. The records, as I have suggested, don’t tell the whole tale, either in quality or in comprehensiveness. For instance, our leading lirico-spinto of that time can be heard in one complete operatic role, and that, of all unlikely chances, is Purcell’s Dido (Track 8). The set is worth looking out (the Sorceress of Edith Coates is also not to be ignored). It is not the modern idea of how Purcell should sound, but at this date, it can be rather refreshing to hear a mature woman (as opposed to a mature schoolgirl) in the part.

From the more standard repertoire, the Trovatore arias are good examples of Hammond’s work as a Verdi soprano—in the Act 4 aria she follows the score’s markings faithfully and phrases with marvellous control. Tatyana’s Letter Scene in Yevgeny Onegin (Track 1) reminds us of her successes in the Soviet Union, and of course there is the unforgettable ‘O my beloved father’ (from Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi) which sold a million copies and in 1969 won the coveted award of an EMI Golden Disc.

The book is a spirited autobiography: A Voice, a Life (Gollancz,1970). In it she tells of that largely forgotten early phase of her career which seemed about to take her to La Scala—and from there who could tell?—when war broke out and left all to be built up afresh. She is very good on wartime conditions for a singer in Britain; at one stage, she says, she didn’t sleep in a bed for a month. She was, one thinks repeatedly while reading, a “sport”. After singing, her great passion was golf; and at the end of the book, looking back over the whole story, she concludes: ‘I have had a wonderful innings’. Not a bad life span either − she died at the age of 84 − for one whose retirement had been forced upon her by a heart condition 31 years earlier.

JOHN STEANE