PUCCINI’S LITTLE WOMEN

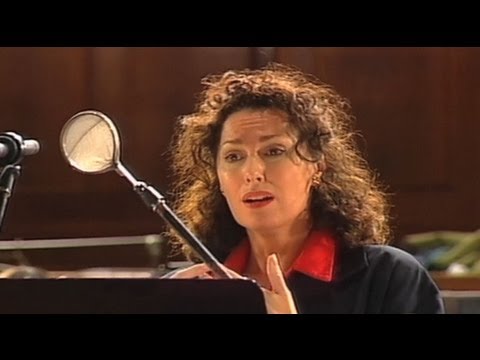

Puccini famously liked to write about ‘little women’, but he gave them ‘big’ music, which is one thing that makes Cheryl Barker so ideal an interpreter of his soprano roles. Her appearance in Baz Luhrmann’s production of La bohème enchanted not just audiences in Australia, but countless fans worldwide on video and DVD. It is politically incorrect to remark on such matters, but the most appealing presence revealed in that Bohème has been no hindrance to a successful career the world over, making her visually well suited to these ‘little women’.

More important—and reactions to voices have to be highly personal—her lyric soprano, with an indefinably sweet vibrancy built in to the tone, adds immeasurably to her appeal. With that vibrancy comes a sense of vulnerability, which helps her bring the characters alive in both vocal and dramatic terms. But there is nothing vulnerable about her actual voice: her lyric sound is moving to the dramatic.

She has long experience as Butterfly, a ‘bigger’ sing than it looks, and she has recently added Tosca, just as big a sing, to her repertory to great acclaim in London. One day she may sing Turandot, but not yet awhile: Liù, the most vulnerable of all Puccini’s ‘little women’, might have been written for her.

This most welcome disc allows her to present an overview of Puccini’s women from the very beginning. His first opera was Le Villi (1884), a version of the Giselle legend, and notable for including a chorus of male Villi. Anna is the Giselle figure, and her first aria, ‘Se come voi’ (Track 1), is an appropriately innocent two-verse song, at the end of which she places a bunch of forget-me-nots on the suitcase of her betrothed, Roberto, who is leaving on a journey. It proves to be a long journey, and while he is away Anna dies of a broken heart. When he returns, he is forced by the Villi to dance unto death.

Puccini’s second opera, Edgar (1889), is saddled with surely the worst libretto ever devised by the mind of man (in this case Ferdinando Fontana). It was a complete flop, and Puccini tried to save it with ruthless cuts, which only served to render it yet more incoherent. Many years later he sent a copy of the score to his friend Sybil Seligman with comments in the margin. ‘This is good,’ he wrote next to ‘Addio, mio dolce amor’ (Track 2), and he was right: to a solemn and supple melody, the heroine Fidelia mourns at the side of Edgar’s coffin, praying to him to wait for her. But Edgar is not dead, merely disguised as a monk. Later he cries out ‘Edgar lives!’ to general consternation. ‘A lie,’ Puccini wrote in the margin, and he was right again.

Despite a none-too-carefully constructed libretto, in which at least eleven people had a hand, Manon Lescaut (1893) is the first of Puccini’s operas to win a place in the repertory, simply on the strength of its musical invention: it is one of the most intricately organised scores he wrote, with almost Wagnerian manipulation of leading motives and—for singers—dangerously sumptuous orchestration. ‘In quelle trine morbide’ (Track 3), Manon’s ‘bird-in-a-golden-cage’ aria, is one of the composer’s most unstrained outpourings of pure melody, with a pair of harmonic side-steps to give it extra lift. ‘Sola, perduta, abbandonata’ (Track 4) finds Manon, exiled from France for immorality, alone in the deserts of Louisiana (swamps would be more likely, but neither the Abbé Prevost, on whose novel the opera is based, nor Puccini, was too hot on topography). Accompanied by the faithful Des Grieux, she has escaped from prison and while he goes in search of water laments a fate she is not going to take lying down: her thrice repeated ‘Non voglio morir’ is one of these ‘little’ women’s most spirited musical gestures of defiance. The orchestra symphonically interweaves themes from earlier acts and happier times into a powerful tone poem of desolation and despair.

If the term ‘verismo’, or ‘realism’, has any meaning (is not realism just one element of theatrical illusion?), then it resides in La bohème (1896). The arias, in which two young people introduce themselves to each other in the first act, are nothing if not ‘real’, with Mimì answering Rodolfo’s slightly boastful autobiographical sketch with one surely more truthful (Track 5). What emerges from it is vulnerability, shyness and—over-whelmingly—the fact that she is lonely, in which case she has maybe selected the wrong man for company. Even more ‘real’—unbearably so—is her ‘Farewell’ in the third act (Track 7). The trivial, everyday mechanics of ending a relationship are depicted with unsparing truthfulness, and the tender modulation framing her offer of the bonnet as a keepsake is one of Puccini’s most merciless assaults on the tear-ducts. We have all been there.

The relationship of Musetta and Marcello breaks up regularly, and the Waltz with which she wins him back for the nth time (Track 6) focuses on the physical attractions she knows he cannot resist; it is only later in the opera that she is revealed as a highly aware, mature and warm-hearted woman.

‘Vissi d’arte’ in Tosca (1900) (Track 8) is seen by some as a bit of a problem. The second act, and indeed everything that has gone before, is all action, but suddenly everything grinds to a halt and the heroine sings an aria. In the Gran Scena Opera Company di New York’s hilarious parody, Scarpia simply settles down in his chair and goes to sleep, and it has been suggested that it should be cut and sung as an encore after the final curtain. But it is of course a pivotal point in this complex and undervalued study of sin and retribution. Tosca has been presented to us as a deeply religious woman. In the aria she asks how God can have rewarded her years of devotion by putting her in so gruesome a situation; it is as near as makes no matter to that most terrifying of moments, a loss of faith. (When the immortal Eva Turner recorded the aria, it sounded as though she were giving the Almighty a jolly good dressing-down.)

And the pivot turns a religious woman into a murderess. Be all that as it may, ‘Vissi d’arte’ is a marvellous tune, and at its climax affords interpreters untold opportunities—eagerly seized by Barker—for expansiveness and delicacy of phrase.

The three extracts from Madama Butterfly (1904) mark separate stages in the ritual destruction (some would say self-destruction) of a trusting human being, a ritual in which the arch-manipulator Puccini involves the audience. In ‘Un bel dì’ (Track 9), Cio-Cio-San imagines the moment when Pinkerton, the husband who has deserted her, returns—something the audience has known will never happen from the very first scene. It is in the form almost of a da capo aria, ABA with coda; the return of the big tune comes with the words ‘so as not to die’ of joy at the moment of meeting. Die she indeed will, but not of joy. In ‘Che tua madre’ (Track 10), the American consul has just asked her what she would do if Pinkerton didn’t come back, and she answers indirectly through her child: either beg, singing and dancing in the streets, or die. Death would be her choice. In the final act, her servant Suzuki tries to forestall the inevitable by pushing the child on to join his mother, but after telling him she is sacrificing herself to ensure his future, she blindfolds him and cuts her throat (Track 11).

Puccini undertook the composition of his operetta La rondine (1917) somewhat cynically, both as a money-spinner and as part of a dispute with his publishers, Ricordi (he wrote it for a rival house). That said, he lavished enormous care on a second-rate libretto, two parts Traviata to one part Manon, and the score is as subtle as it is highly perfumed.

The only possible criticism of ‘Ch’il sogno di Doretta’ (Track 12) is that it is too short and you only get the big moment once, a problem easily solved on CD. In ‘Ore dolce’ (Track 13) we hear the first of the many waltzes with which the work is studded; the heroine recalls a carefree evening out in the cafés of Paris.

Suor Angelica is the least popular panel in Puccini’s triptych Il trittico (1918), but to my mind the best: the instrumentation has truly Debussy-esque colour and transparency. Angelica has been placed in a convent by her aristocratic family, shamed by her having had an illegitimate child. Her aunt, the Princess, who could give Turandot a lesson or two in calculated cruelty, comes to tell her that she has been disinherited and, casually, that her son has died.

In ‘Senza mamma’ (Track 14), Angelica imagines his lonely death and longs for the time when her own demise, shortly to follow, will reunite them. Here, Puccini’s gift for melody achieves a tragic poignancy unsurpassed anywhere in his oeuvre. In quite another context, melody is just as powerful in ‘O mio babbino caro’ from Gianni Schicchi (Track 15), the comic final panel of Il trittico. Lauretta schmoozes her father into helping her fiancé’s family to forge Buoso Donati’s will, a crime for which Dante sentenced Schicchi to his Inferno, but a crime committed in the interests of young love and one of which the audience is invited to approve (and invariably does).

The two arias for the servant girl Liù in the unfinished Turandot (1926) are grist to the mill of every lyric soprano. She is the very antithesis of Princess Turandot, selfless, loving and tender. In ‘Signore, ascolta’ (Track 16), she joins the company in begging Calaf not to take up the challenge of Turandot’s riddles, shyly confessing her love in the process. The pianissimo floated top A–flat and B–flat at the end have truly ethereal beauty. In ‘Tu che di gel sei cinta’ (Track 17), she offers a direct challenge to Turandot, prophesying that the Ice Princess herself will melt into love before killing herself in an act of self-sacrifice to conceal Calaf’s identity. With her death, Puccini’s contribution ends, and completion has been highly resistant to the efforts of others.

The disc ends with the folksong-like ‘E l’uccellino’ (Track 18), written for the child of a friend who died soon after his marriage and before the child was born, and the song ‘Sole e amore’ (Track 19), dating from 1888, which, if it sounds familiar, indeed is: Puccini exhumed the melody for the quartet at the end of the third act of La bohème. He was never one to waste a good tune

RODNEY MILNES