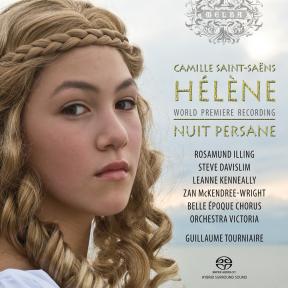

Helen of Troy: The Eternal Allure

In the Southern Peloponnese, just outside Sparta, there is a small hill. A broken-down shrine nestles on its peak. Buffeted by soft, warm winds this feels a charmed place. A silver river snakes through the valley below, the Taygete mountains glisten in the distance – snow-tipped long into the summer. It was here, in the heat of the day and the chill of night, that men and women throughout antiquity would come to worship their half-divine ancestor: the World’s Desire, Helen of Troy.

This is the hill where Saint-Saëns opens his Hélène. It was here that Menelaus, and his wayward wife, Helen, Queen of Sparta were believed to have lived in palatial splendour. Homer describes the gorgeousness of their palace-home:

the sheen of bronze,

the blaze of gold and amber,

silver, ivory too, through all this echoing mansion!

Surely Zeus’s court on Olympus must be just like this.

But Saint-Saëns starts his action when all that calm, comfortable, domestic luxury is about to be blown apart. Paris, a young Trojan prince, has travelled across the Aegean (in the Bronze Age, diplomats did indeed sail the Aegean and Mediterranean to do business with overseas aristocrats) to Sparta.

He brings conciliatory gifts for the Spartan King, but is enraptured by Menelaus’ Queen:

Glory to the noble Queen

Helen with the white arms.

Some sources believe Paris came ready to steal Helen away; that he concealed, in his black-bottomed boat, spears under olive branches.

Saint-Saëns was fascinated by Ancient Greece, and he was fascinated by this dread, universally familiar moment: when the wrong two people fall in love. Helen and Paris encapsulate all that is wonderful and terrible about human relationships: the passion, the pain, the glory and sublime selfishness of loving. It is why, from the moment that Helen enters the written record 28 centuries back in Book 2 of Homer’s Iliad, she never leaves the human radar. Women are usually written out of history: Helen, and her fatal beauty, have been written in.

Helen appears in prodigious guises through the literary, material and cultural record: a half-divine force of nature; a flesh and blood Greek princess; a fantasy whore. Her adoration was widespread: in Egypt gold cosmetic platters were inscribed with her name; at Rhodes breast-shaped cups were dedicated in her honour; you can still pay homage at Loutros Elenis, Helen’s Spring, near Corinth, where the mineral waters are thought to have restorative powers. Helenic ritual sites abutting springs is one of the clues that Homer’s Helen was perhaps grafted on to a prehistoric cult of a fecund nature goddess. But then the queen of nature’s crown slips, and instead of representing a primeval life-force, a valued female sexuality, she is branded a tart, a slut, a femme fatale.

For many in the canon of Western art, Helen is indeed a ‘bitch-whore’ (Euripides), a ‘nasty scheming little bitch’ (Homer), ‘a strumpet’ (Shakespeare): yet Saint-Saëns is wonderfully sympathetic to one of the most universally despised of women. He sees young Helen, not as a man-eater, not as the she-devil in Goethe’s Faust that ‘sucks forth men’s souls’ but as a victim of Aphrodite and Eros’ poisoned love-drugs. And so we meet a frightened young Queen, one who is bruised, scared, alone, fighting against a dreadful fate. For Helen senses, as we with the benefit of history’s hindsight already know, that just one kiss will drag the heroes of the known world in her bloody wake, across the Aegean to die fighting outside the walls of Troy.

Saint-Saëns wrote his libretto on an Egyptian island. His lovers speak to us from the isle of Kranai, a jagged rock just off the coast of Gythion south of Sparta: here the fugitives spent their first night together. Kranae means ‘rocky’ – if you visit today you’ll be hard-pressed to walk across the islet’s razor-sharp volcanic surface. It is a fitting setting for Helen and Paris’ ancient passion. The passion of the composer – inspired perhaps in part by his salt-licked Eastern Mediterranean hideaway – blazes out from the score.

But unfortunately Hélène arrived in a Europe that had already glutted on the neo-classical oeuvre. By the late 19th century, Egypt, rather than Greece, was the flavour of the month. If Saint-Saëns had in fact taken Helen to the Egyptian coast (where she ends up in some versions of the myth while the Greek and Trojan heroes fight over a ghost, a fantasy, ‘a butterfly’s flicker, a wisp of swan’s down, an empty tunic’ as the 20th-century Greek poet George Seferis put it) his production may have had more enduring commercial success. For some, by this stage, ‘The Age of Heroes’ has become a little ludicrous. Offenbach’s operetta La belle Hélène (first performed 1864) which treated the whole affair like a bedroom farce was a roaring success. Saint-Saëns was horrified. ‘The collapse of good taste’ he bewailed.

For a while, Hélène’s star burnt bright. Commissioned for Nellie Melba, the Australian-born, internationally-renowned diva was indeed a second Helen, attracting to her performances the beau monde. To be cast as the most beautiful women in the world is of course, not a little flattering. But there is a problem. The eternal allure of Helen is that we do not know what she looked like, we have never seen her face. Ineffable, she can be every man’s, every woman’s idea of physical perfection. She is the perfect fantasy. But once made incarnate, Helen has the potential to disappoint as much as to delight.

The French painter Gustave Moreau, working in Paris at the same time as Saint-Saëns, recognised this. Canvases of Helen still litter his studio on rue de la Rochefoucauld (now a museum dedicated to his life and work) and in one ‘Helen at the Scaean Gates’ he shows Helen, faceless. Troy melts with flames behind her. It is one of the most apposite, and heart-chilling, images of Helen I have ever seen.

In this Hélène Paris and Helen are shown a prophetic vision of the flames that their love will bring to Troy: yet they choose to walk toward them.

So the lovers sail eastwards, bewildered. Whose fault is all of this? The gods? Their own? Or some more fateful, inescapable, turning of the world, a malign revolution that crushes those in its path? However you judge Helen, whether you believe her to be whore or goddess, Saint-Saëns recognises the one thing she always represents: the power of human desire; the yearning, the restless longing that we sustain for that which we do not have. The young girls of Sparta would worship Helen all night up at her hilltop shrine to try to summon up some of her ‘kharis’, her grace, her sexual allure, her power to catalyse desire, out of the earth. As they did so they sang enchanting, haunting songs.

Helen was first evoked in the poetic rhapsodies of Homer. We remember her, perhaps, most poignantly, as a line of verse: Christopher Marlowe’s ‘face that launched a thousand ships’. The revival this lost work of Saint-Saëns’ adds to the Helenic canon – I would argue in its strongest form – in words and music leaves the world a richer place.

BETTANY HUGHES

Saint-Saëns: The Lure of the East

Saint -Saëns succumbed, like many Frenchmen of his generation – poets, musicians, painters – to the lure of the east, to the world of harems, exotic veils, cruel potentates and snake-charmers. But unlike most others of similar tastes his was not an armchair passion; he was a constant visitor to North Africa and the Middle East. He found in Egypt or Algiers a refuge from the frustrations and petty hostilities of Parisian life, and he liked the solitude of the desert for composing. A number of his works evoke the Muslim world, but none with more potency than Nuit Persane, the dramatic cantata he fashioned from an earlier song cycle Mélodies persanes, settings of six poems by the obscure poet Armand Renaud he had composed in 1870. According to Saint-Saëns’ original published score, ‘Renaud’s work evokes a particular vision of eastern life as glimpsed through a dream, in the form of a fatal succession of passionate feelings: desire, love, grief, the fury of war, world-weariness with omnipotence, ending in mystical madness and oblivion.’

Restless as always, Saint-Saëns spent the winter of 1890–91 first in Spain, then sailed via Suez to Ceylon, then back to Cairo, where he completed his fantasy for piano and orchestra entitled Africa. After a brief return to Paris, he went to the Canaries, then to Algiers, then to Naples, then to Geneva and Paris. A conversation in Paris with the conductor Colonne planted in his mind the idea of orchestrating his earlier songs, and this in turn developed into a rounded dramatic form, with settings of two extra Renaud poems (La fuite, CD2 track 4 and Les cygnes, track 7) and a narration (over music) to link them. The final work, which he returned to Algiers to work on, is an exotic drama that tells of a young girl confined in a harem. She dreams of the gallant lover who will ride to her rescue. He arrives and carries her off to a land of bliss which is nonetheless tainted with the odour of death. She dies, causing her lover to wreak a violent revenge on mankind. Remorse leads him to join the whirling dervishes, in whose company he sinks into an opium haze and spirals into nothingness.

The intensely decadent atmosphere of Renaud’s poems is fueled by rich vocabulary and evoked by Saint-Saëns’ marvellously colourful orchestration. The four parts of the drama are themselves divided into shorter sections:

I La solitaire

Prélude

La brise

La solitaire

La fuite

II La vallée de l’union

Prélude

Au cimetière

Les cygnes

III Fleurs de sang

Prélude

Sabre en main

IV Songe d’opium

Prélude

Tournoiemen

In La brise (track 2) the women’s chorus describes the life of the harem on a modal scale with a tambourine in the background. No sooner has La solitaire (track 3) called out with some vigour for the lover who will save her than he arrives at a gallop, and in La fuite (track 4) they flee together. Saint-Saëns had the Ride to the Abyss from Berlioz’s Damnation de Faust in his ears when he wrote this brilliantly evocative ride. The chorus, as roses and nightingales, wish them on their way.

The lovers’ union is essentially melancholy, as we hear in the flute and cor anglais’ melody at the start of Part II (track 5), and the tenor’s song, Au cimetière (track 6), with its throbbing harp accompaniment, reminds us of death, the inescapable partner of passion. Its opening theme, with its chromatic inflection on the word tombe, is heard throughout the work, always suggesting the conjunction of love and death. But the lovers are permitted a rich, ecstatic love duet, Les cygnes: closing with a reminder that roses are for today, cypresses for tomorrow.

Inevitably she dies. Part III (tracks 8 and 9) is concerned solely with her lover’s furious revenge on all the land with his barbarous hordes ‘like flies’ slaughtering and laying waste.

Part IV opens with a horn solo (track 10) that suggests the lover’s remorse. The theme from Au cimetière haunts him. Grief replaces fury; he joins the whirling dervishes, whose mysterious opium-driven spinning closes the work in a handful of dust.

Extracts from Nuit Persane were performed at the Châtelet, Paris, on 14 February 1892, and the full work was heard for the first time at a concert by the Conservatoire orchestra on 3 January 1897.

Saint-Saëns was as passionate about the northern shores of the Mediterranean as about the southern. The ancient world, both Greek and Roman, absorbed him all his life, and he studied both the literature and the archaeology in depth. He composed a great number of works that treated or evoked Greek mythology or Roman history, often adopting an archaic style by using the ancient modes of the church, widely presumed to have their roots in folk music of the past. Sometimes he even adapted melodies that were themselves supposed to derive from ancient Greek models.

In his opera Hélène, however, he confined himself entirely to the modern style in presenting one of the earliest stories from Greek mythology. His theme was, after all, the conflict between love and duty, familiar from any number of modern operas, and he situated it in the heart of Helen of Troy, the most alluring figure of the great Homeric story. Simply told, Saint-Saëns wanted to explore Helen’s reasons for leaving Menelaus, her husband, King of Sparta, for the Trojan prince Paris, thus unleashing one of the great conflicts of history, the Trojan War. He depicts her as the victim of a destiny that compels her to suffer from an irresistible passion. She is conscious of her feelings but determined to resist them. The intervention of the goddesses Venus and Pallas Athena, one encouraging her to give in to her love, the other warning of the disasters that will ensue if she does, fails to stem the course of destiny, allowing Helen and Paris to sail off to Troy, blissfully afloat on ‘breezes and kisses’.

The image of Helen on the cliff-tops, fleeing from her Spartan palace and wooed by Paris, had been in Saint-Saëns’ mind’s eye for many years before he ever composed the opera. He was also profoundly offended by Offenbach’s frivolous treatment of the same theme in La belle Hélène, a smash hit since its premiere in 1864. In 1903 he was invited to write an opera for the breathtakingly ornate theatre in Monte Carlo whose repertory was one of the most adventurous in Europe. Its director, Raoul Gunsbourg, engaged the finest singers in the world, including, for this new work, Nellie Melba. Saint-Saëns decided to develop his Hélène idea, writing the libretto himself, with help, as he put it, from Homer, Virgil and other classics. He went to Cairo to work on it, but got involved in putting on concerts there. So he moved on to Ismailia, on the Suez Canal, where he found solitude. In 12 days the poem was written before he had to return to Paris. To compose the score he went to Aix-les-Bains, in the French Alps. ‘One should always work thus,’ he wrote, ‘in calm and silence, away from distractions and calls, supported by the grand spectacle of nature, amid flowers and scents’.

The premiere of the opera took place at the Théâtre de Monte-Carlo on 18 February 1904. Within a year it had been heard also in London, Milan and Frankfurt. It was first sung in Paris at the Opéra-Comique in 1905, with a revival at the Opéra in 1919. Since then, like much of Saint-Saëns’ immense œuvre and all his operas except Samson et Dalila, Hélène has had to wait a long time for its well-deserved revival.

In placing the emphasis on destiny as the motivating force of the drama, not passion, Saint-Saëns laid a classical patina over his work and justified a score of faultless craftsmanship that lacks the surging voluptuousness that Strauss or Puccini might have provided. There is nonetheless a richness of melodic invention and of orchestral resourcefulness that betrays the hand of the master.

The opera is constructed as a brief prelude and seven scenes, the first of which is very short with offstage salutes to Menelaus and Helen. The drama really begins in the second scene (CD1, track 3) when Helen, on the cliff-top, fights with her conscience and her awareness of Paris’ allure. Her aria ‘Je vivais, paisible, honorée’ has an aura of sweet lost innocence, but her troubled soul drives her to contemplate hurling herself into the sea. Venus (high soprano) intervenes with a simple message of the power of love (track 4), and her chorus of Nymphs beautifully support her. She assures Helen that she will one day return to Greece. The fourth scene (track 5) is Paris’ wooing, much of it in waltz tempo. At first she rejects his advances, but eventually confesses her love. At that point Pallas Athene (contralto) intervenes with a warning and a vision of the fate that will befall Troy (track 6). Helen and Paris, alone in Scene 6 (track 7), take no heed of the warning, and after an evocative orchestral interlude, they are seen sailing away to their terrible destiny across the Aegean (track 8).

PROF. HUGH MCDONALD